We haven't talked about the euro yet in this blog - and this is something that we will have to remedy soon. But for now, we will focus on the "Greek crisis", as more and more analysts, banks and investors are preparing for a debt restructuring and/or a default.

There are plenty of articles on the subject - however, we will repost an article written by Michael Pettis two years ago, as he probably explains the situation better than everyone else.

When the crisis first started, all the banks were completely against any form of debt restructuring, "haircut", or default. They claimed that this would be disastrous for Greece (i know, i was there, as I am Greek, so i witnessed the events first hand). In reality, the banks knew that Greece is bankrupt, but they also knew that if Greece was allowed to officially declare bankruptcy, and stop paying making payments on its loans+interest, then they (the bankers) would also go bankrupt, as they couldn't absorb these losses.

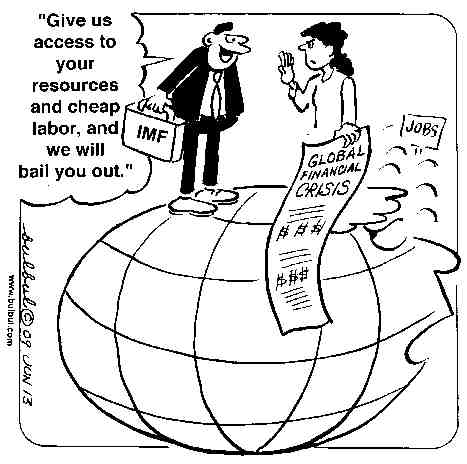

So, they decided to lie about it, scare the population into thinking that a default would be disastrous, and present us with a "solution" that would only increase Greece's debts (The IMF was called in to implement this solution along with the troika and the Greek government, and even according to the IMF's own projections, the Greek debt will only rise after this "solution"). The bankers however liked the plan, as they would receive a lot of bailout money (they are the recipients of those, not the Greek people), and they would also have more time to get rid of all those bonds of the PIIGS nations that cannot be repaid.

But as the bankers are getting all that money and their balance sheets are improving, they are now becoming capable of withstanding those losses. So, they are starting to admit that "a Greek debt restructuring may be necessary after all". Some banks can now withstand a 50% haircut, so they propose a 50% haircut. Some other banks can withstand a 75% haircut, so they propose a 75% haircut, etc. In the end, when they are ready, they will even admit that Greece is bankrupt (100% haircut), but that will only happen when they've received all the bailout money they need to withstand this kind of losses. Until this time comes, their goal is a gradual and controlled bankruptcy.

Here is Michael Pettis on the subject (Jun 24th, 2010):

What might history tell us about the Greek crisis?

The Greek crisis may in many ways seem unprecedented, but of course it isn’t. I think by now everyone already knows that Greece has spent much of the past 200 years – more than half by some counts – in default or in one form or another of debt restructuring, but in fact there are plenty of other periods of sovereign default and restructuring that can tell us something about what is happening and what will happen. I would suggest that there at least five things we can “predict” with some degree of confidence from looking at historical precedents:

1. The euro will not survive in its current form.

We should always have been skeptical about the survivability of the euro. There is a history of currency unions from which we can draw two reasonable conclusions. First, without fiscal integration such as occurred in the US after the Civil War or in the German Customs Union under Prussian dominance, currency unions are no more permanent than other forms of monetary integration, such as adherence to gold or silver standards.

Without robust mechanisms to absorb imbalances that emerge in different parts of the economy, and Europe embodies many very different economies, countries normally are forced to rely on monetary adjustment [the not-so-competitive economies devalue their currencies - my note] . The European currency union eliminates this type of adjustment mechanism, leaving countries with only two, brutally difficult options for adjustment besides opting out – sovereign default or long periods of deflation and unemployment.

So along with very high levels of capital mobility (which Europe possesses to some extent) and labor mobility (of which it has much less), Europe also needed to assign a substantial amount of fiscal sovereignty to some entity. I have already explained elsewhere why I think this was always very unlikely. Difficult as it might be, opting out of the euro is likely to be much less unpalatable for many countries than sovereign default or long periods of high unemployment.

Second, when currency unions are successful, it is almost always during periods of rising global liquidity and expanding international capital flows. No currency union has been able to survive the great monetary contractions that spell the end of a globalization period. The 19th Century’s Latin Monetary Union and the Scandinavian Monetary Union, to take the most obvious examples, were both once considered great successes, but were forced into retreat when global monetary conditions turned sour.

So when will countries opt out of the euro? Ernest Hemingway once described the process of going broke as “Slowly. Then all at once.” That is not a very precise description, I know, but I would guess that support for the euro will erode very slowly until suddenly it seems inevitable and then the process will happen breathtakingly quickly.

2. This is the big one

One of the myths that we often hear repeated is that financial crises have been occurring with increased frequency in the past one or two decades. I think we only believe this because we remember the big crises of the past, which seem to occur every twenty to thirty years, and then look back all crises of the past two decades – Mexico in 1994, East Asia in 1997, LTCM and Russia in 1998, Brazil in 1999, the Internet Bubble in 2000, the Sub-Prime crisis in 2007, and Greece in 2010 – and conclude that there are an awful lot more crises nowadays.

But in my book, The Volatility Machine, I made sure to distinguish between the short-term liquidity crises that occur within globalization cycles, of which there are a lot and seemed to occur every two or three years, and the long-term liquidity contractions that spell the end of each of the major globalization cycles. The former can be brutal, but they are usually short-lived and the overall market recovers very quickly.

So, for example, although most of us know that the world experienced a deep and long-lasting crisis in 1873, which began a long period of contracting international trade, reduced capital flows, and the massive bankruptcies of the high technology companies of the period, including most notably the railroads, very few people seem to know about the Overend Gurney crisis of 1866, which seemed pretty horrific at the time but from which the markets recovered fairly quickly. Likewise the great and well-known LDC debt crisis beginning in 1982 was preceded by several smaller crises, most importantly I think in 1976 by a Mexican peso crisis, which two years later had all but been forgotten by the market.

In my opinion the current set of crises, beginning with the sub-prime crisis in the US and spreading throughout the world, is not a short-term liquidity crisis like LTCM, the Asian Crisis, or the Mexican crisis of 1994. I think this is likely to be one of those big events, one that represents a major re-adjustment in the world during which time the massive imbalances that had been built up during the long globalization cycle that started around the late 1980s and early 1990s are finally worked out.

Not only will Greece, in other words, get worse, but it is by no means the end of the crisis. A lot more countries in Southern Europe, Latin America and Asia are going to be caught up in this before it ends.

3. The European crisis will be accompanied by a trade shock.

In the early 1980s Latin America countries were suddenly cut off from funding during what was subsequently called the LDC Debt Crisis, or the Lost Decade. These countries had been running large current account deficits, and of course current account deficits require capital account surpluses. These surpluses were financed by the the huge petrodollar recycling of the 1970s, when commercial banks around the world made staggeringly large loans to many developing countries.

Of course after 1981-82 it became clear that the loans exceeded the repayment capacity of the borrowing countries, and suddenly financing dried up – almost overnight. What’s worse, the debt crisis had already been preceded by flight capital, so that when financing dried up, a capital account surplus quickly became a capital account deficit. Of course once Latin America began to experience capital outflows, its trade deficit necessarily had to become a trade surplus. This is exactly what happened.

The deficit countries of Europe, whose combined trade deficits are nearly two-thirds the size of the US trade deficit, will also be forced into a rapid contraction in their trade deficits for the very same reasons – they are going to find it hard enough simply to refinance themselves, let alone receive net capital inflows. Without a capital account surplus, however, they simply cannot run current account deficits. This contraction must, one way or another, be absorbed by the very unwilling rest of the world. I describe what this will entail in a May 19 entry.

4. The economic recovery in the countries hit by crisis will not begin until they are recognized as insolvent and receive debt forgiveness from their creditors.

Preceding every sovereign default is the fiction that the obligor country is simply facing a short-term financing problem, and that with a lot of discipline and a little bit of good will it will be able to work its way out of the crisis. During this period a number of restructuring “solutions” are proposed – all of which involve increasing debt, and often in the most financially destabilising way – which inevitably make the final resolution of the crisis much more difficult and which sharply raise financial distress costs. The most notorious recent example of these terrible “solutions” was Argentina’s disastrous debt swap in 2001, in which it dramatically increased the country’s total obligations while it desperately tried to maintain the fiction that it could somehow grow its way out of its impossible debt burden.

Greece, and probably two or three other countries, simply cannot repay their outstanding debt amounts. Ultimately they are going to default, and then in the restructuring process they will receive enough debt forgiveness that allows them to return to a sound footing and with a reasonable repayment prospect. But as long as they maintain the pretence that they can and will repay the full outstanding amount, and struggle with the burden, the resulting distortions in the economy will mean that businesses will disinvest and the country will not grow.

Historical precedence makes it clear that as long as the sovereign borrower is forced to struggle with an unrepayable debt burden, it will not grow. Eventually, as has happened in nearly every previous case, creditors and borrowers will acknowledge reality and will work out a debt forgiveness plan that will allow the economy to return to growth. Until then, expect weak growth, high unemployment, and constant battles over debt.

How long will it take for the world to recognize the inevitable? That leads us to the fifth thing we can learn from historical precedents.

5. Greece’s insolvency will not be recognized for many years.

When most of the obligations of an insolvent sovereign were widely dispersed among a wide variety of bondholders, market forces acted relatively quickly to force debt forgiveness. Defaulted bonds trade at deep discounts, and it is a lot easier for someone who bought the debt at one-quarter its face value to agree to 50% debt forgiveness than for someone who made the original loan.

But things are different with the current crop of insolvent European sovereign debts, as they were with the sovereign loans of the 1970s. They are heavily concentrated within the banking system, and the banks cannot recognize the losses without themselves collapsing into insolvency.

That cannot be allowed to happen. The LDC debt crisis of the 1980s raged on nearly a full decade – a decade of stopped payments, capital flight, and agonizingly low growth – before creditors formally acknowledged that most struggling borrowers could not repay their debt and would need partial debt forgiveness. The first formal recognition of debt forgiveness occurred with Mexico’s Brady Plan restructuring in 1990. Growth returned to most countries only after it became clear that they would receive debt forgiveness.

Why did it take so long? Were the banks stupid? No, banks knew full well that they weren’t going to get their money back as early as the mid-1980s, but to have acknowledge this would have required them to set aside more capital to absorb the losses than most of them possessed. The recognition of the obvious had to wait nearly a full decade so that banks could build a sufficient capital cushion to absorb the losses.

So too with the European crisis. Much of the Greek debt is held by European banks, and they simply do not have enough capital to absorb losses on Greek debt, let alone if Greece were to be joined by Portugal, Spain and others. The banks will need first to rebuild their capital bases before they can admit the obvious, and this could take several years.

So we are condemned to spend much of the next decade postponing a resolution of the crisis while banks rebuild their capital base. Until they do, we will all pretend that Greece isn’t insolvent and that other European countries will not face a crisis. Meanwhile none of these countries will be able to grow.

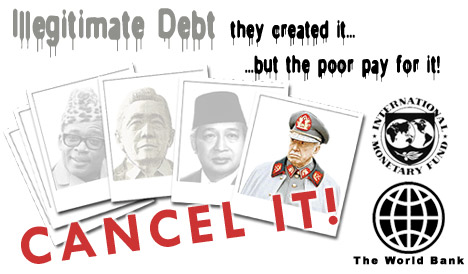

Odious debt - from Wikipedia:

In international law, odious debt is a legal theory that holds that the national debt incurred by a regime for purposes that do not serve the best interests of the nation, should not be enforceable. Such debts are, thus, considered by this doctrine to be personal debts of the regime that incurred them and not debts of the state. In some respects, the concept is analogous to the invalidity of contracts signed under coercion.

The doctrine was formalized in a 1927 treatise by Alexander Nahum Sack,[1] a Russian émigré legal theorist, based upon 19th-century precedents including Mexico's repudiation of debts incurred by Emperor Maximilian's regime, and the denial by the United States of Cuban liability for debts incurred by the Spanish colonial regime.

According to Sack:

When a despotic regime contracts a debt, not for the needs or in the interests of the state, but rather to strengthen itself, to suppress a popular insurrection, etc, this debt is odious for the people of the entire state. This debt does not bind the nation; it is a debt of the regime, a personal debt contracted by the ruler, and consequently it falls with the demise of the regime. The reason why these odious debts cannot attach to the territory of the state is that they do not fulfil one of the conditions determining the lawfulness of State debts, namely that State debts must be incurred, and the proceeds used, for the needs and in the interests of the State. Odious debts, contracted and utilised for purposes which, to the lenders' knowledge, are contrary to the needs and the interests of the nation, are not binding on the nation – when it succeeds in overthrowing the government that contracted them – unless the debt is within the limits of real advantages that these debts might have afforded. The lenders have committed a hostile act against the people, they cannot expect a nation which has freed itself of a despotic regime to assume these odious debts, which are the personal debts of the ruler.