This graph (via The Economist) shows how much tuition fees have risen in US universities during the last few decades.The Economist article was published a couple of years ago, and it correctly pointed out that:

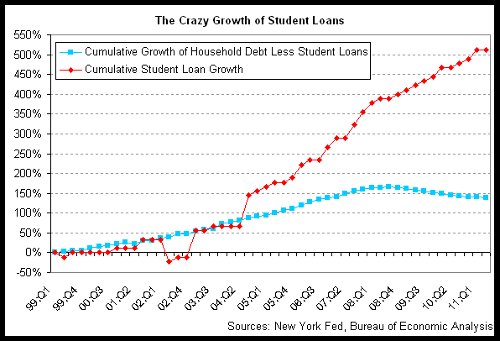

For decades, college fees have risen faster than Americans’ ability to pay them. Median household income has grown by a factor of 6.5 in the past 40 years, but the cost of attending a state college has increased by a factor of 15 for in-state students and 24 for out-of-state students. The cost of attending a private college has increased by a factor of more than 13 (a year in the Ivy League will set you back $38,000, excluding bed and board). Academic inflation makes most other kinds look modest by comparison. Students may not be getting a good deal in return.No shit Sherlock. Back in 2010, Student-Loan Debt Surpassed Credit Card debt for the first time ever (source: WSJ), and Mark Kantrowitz, publisher of FinAid.org and FastWeb.com was quoted as saying that:

“The growth in education debt outstanding is like cooking a lobster,” Mr. Kantrowitz says. “The increase in total student debt occurs slowly but steadily, so by the time you notice that the water is boiling, you’re already cooked.”It gets worse: About a month ago, Student-Loan Debt Topped $1 Trillion, and this whole "bubble in education" thing gathered even more attention by the media.

There is of course a similar situation in a lot of western countries (England being the most notable example), but the US situation is far more important and big.

America was the world's superpower, and its economy was the world's most productive economy for a long time after the end of WWII. More and more Americans started attending college, as it was a great way to achieve "upword social mobility" (ie you could get a (good) job easier).

After all, the economy was booming, as we were in the "creative" part of the "creative destruction" process: Capitalism went through a major crisis (Crash of 1929), but after the end of WWII, we needed to rebuild...almost everything (because almost everything had been destroyed during the war).

So, jobs were relatively easy to come by, and if you had a college degree, you were almost guaranteed a good job, a good income, and a "middle-class lifestyle".

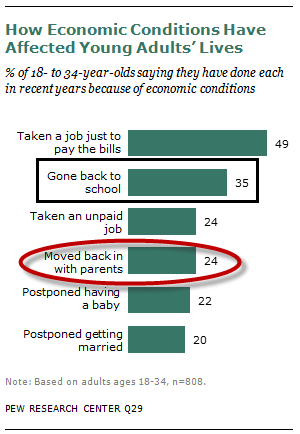

Yes, life was good. But as we have explained before, America started falling behind in its competition with the other powers (especially Japan, Germany, and now China). Production is being outsourced to China, and wages and dropping rapidly, in order to compete with the Asian workers. And now that giving away loans as a way to mask this process cannot continue anymore, things are really bad for the younger generations of workers. How are they even gonna repay these loans, if they can't find a job? And even if they can, odds are this job will not pay enough money to cover these loans.

Is it no accident that some capitalists are already calling them "the lost generation", as they have to be "sacrificed", in order for a new generation of workers to be born, a generation of

In a New York Times article, published a few years ago, there were a few interesting -and revealing- quotes about this whole situation, citing Ms Munna, a 26-year-old graduate of NY University, who plainly states that “I don’t want to spend the rest of my life slaving away to pay for an education I got for four years and would happily give back, it feels wrong to me.”

Like many middle-class families, Cortney Munna and her mother began the college selection process with a grim determination. They would do whatever they could to get Cortney into the best possible college, and they maintained a blind faith that the investment would be worth it.

Today, however, Ms. Munna, a 26-year-old graduate of New York University, has nearly $100,000 in student loan debt from her four years in college, and affording the full monthly payments would be a struggle. For much of the time since her 2005 graduation, she’s been enrolled in night school, which allows her to defer loan payments.

[...] Over the course of the next two years, starting when she was still a teenager, she borrowed about $40,000 from Citibank without thinking much about how she would pay it back. How could her mother have let her run up that debt, and why didn’t she try to make her daughter transfer to, say, the best school in the much cheaper state university system in New York? “All I could see was college, and a good college and how proud I was of her,” Cathryn said. “All we needed to do was get this education and get the good job. This is the thing that eats away at me, the naïveté on my part.”

There are a lot of articles about "the education bubble", and education is a topic of huge significance, that we will talk about in future posts. But, if you really want to understand how "the education bubble" was created, all you have to do is think of education like an investment (yes, I know that education should help you develop "critical thinking", "moral values" and all that stuff, but why on earth would the ruling class want you to develop that? They only "moral values" they want you to learn are obedience to your masters, market values, like "everything is for sale" and all that stuff, and of course the necessary technical knowledge to make you more productive in your area of expertise).

Anyway, as I was saying, all you have to do is think of education like an investment: You invest time and money in order to "weaponize" yourself with "marketable skills" and be ready to face the competition when you finally enter the labor market "arena". Capitalism in its purest form forces the workers to compete against each other - and "only the strong survive". In today's global labor market, the Asian workers are simply..."destroying the competition". As for the western workers, only a few are "good enough" - the rest are simply redundant. Their "blind faith that the investment would be worth it", and that "all we needed to do was get this education and get the good job" was misplaced (at best).

Capitalism is based on faith and speculation - these students and their families speculated that getting a college degree was a good investment, because for many years now, it had been the key to securing a good job. So, it was OK to get a student loan, because they speculated that they would be able to repay it + live a comfortable life in the future.

But the returns on their investment were not as great as they thought. There are other competitors, especially in Asia, that can (generally) do the same things as them, maybe even more, and they are also willing to worker longer hours for less money. Not to mention the fact that some western education systems are crappy (we shall discuss this in greater detail the future). So, not a lot of western students will be able to get a job and repay their debts. Of course, the western businessmen are quite happy to go along with this, because they get to increase their profits, due to the lower labor costs. But the workers will suffer - debt slavery, unemployment and poverty is their future, and on top of it all, they were caught completely off-guard and are not ready to fight back, as most of them were under the illusion that "all we needed to do was get this education and get the good job"...

Oh, and by the way, here's an interesting piece of news, in case you were thinking of defaulting on your student loans:

Unable to find a job as a music teacher in the current economic crisis, he eventually went into default on his loans, which included Stafford, Perkins and private bank loans. Then this year, he decided to go on to earn a PhD, which would make it possible for him to get hired in his field. He applied to a top-rated university in the Northeast, but when it was time to send his school transcripts, Temple froze him out. “They said as long as I was in default on my loans, they would not issue a transcript!” says Rodriguez.

A spokesman from Temple confirms that it is school policy to withhold official transcripts from graduates who are in default on their student loans.

+ A few interesting articles that weren't mentioned in the post, but are worth a read:

- New graduates will have to work until 71 before qualifying for state pension (guardian)

- Fifth of new graduates unemployed (Independent), but what about the others? Well, A third of graduates take low skilled jobs, according to the Telegraph.

- If America Spends More Than Most Countries Per Student, Then Why Are Its Schools So Bad? (BusinessInsider)

- Chinese Applicants Flood U.S. Graduate Schools (WSJ)

- What Should You Know About the Quebec Student Strikes and Occupations? (nextnewdeal)

- The US schools with their own police (guardian)

- MUST READ: The Astounding Failure of the US Educational System - John Taylor Gatto (ZeroHedge)