This blog hasn't been updated in approximately two months (which feels like a lifetime in our "fast-changing" world). But hopefully I will have more time from now on - and for my first post after such a long while, the choice was easy: On April 20, 1914, a great event happened in USA, an event that is even known to an foreigner like me. And yet, it has been forgotten by (almost) everyone there, judging by what the media are (not) talking about today, on this historic anniversary of

the Ludlow Massacre. And you know what they say about those who forget about their past - they are bound to repeat it.

So what was this "Ludlow Massacre"? It was one of the greatest battles in the history of class war in USA. And since it was named "massacre", you've probably guessed that it was much more brutal than teargassing the OccupyWallStreet protestors - it was more in the "Game Of Thrones" category of hurting your opponent. And this is probably why the big media don't like talking about it: It is much easier to "manufacture consent" when you omit some little details, like the

killing annihilation of "a few workers" who dared to go on strike.

Here are the details, from wikipedia:

The Ludlow Massacre was an

attack by the Colorado National Guard on a tent colony of 1200 striking coal miners and their families at Ludlow, Colorado on April 20, 1914.

The massacre resulted in the

violent deaths of between 19 and 25 people; sources vary but all sources include two women and eleven children, asphyxiated and burned to death under a single tent. The deaths occurred after a day-long fight between strikers and striking workers. Ludlow was the deadliest single incident in the southern Colorado Coal Strike, lasting from September 1913 through December 1914. The strike was organized by the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) against coal mining companies in Colorado. The three largest companies involved were the Rockefeller family-owned Colorado Fuel & Iron Company (CF&I), the Rocky Mountain Fuel Company (RMF), and the Victor-American Fuel Company (VAF).

|

| Red cross workers on the strikers' camp after the attack |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In retaliation for Ludlow, the miners armed themselves and attacked dozens of mines over the next ten days, destroying property and engaging in several skirmishes with the Colorado National Guard along a 40-mile front from Trinidad to Walsenburg. The entire strike would cost between 69 and 199 lives, described as the

"deadliest strike in the history of the United States".

The Ludlow Massacre was a watershed moment in American labor relations. Historian Howard Zinn has described the Ludlow Massacre as

"the culminating act of perhaps the most violent struggle between corporate power and laboring men in American history". Congress responded to public outcry by directing the House Committee on Mines and Mining to investigate the incident.

Its report, published in 1915, was influential in promoting child labor laws and an eight-hour work day.The Ludlow site, 12 miles (19 km) northwest of Trinidad, Colorado, is now a ghost town. The massacre site is owned by the UMWA, which erected a granite monument in memory of the miners and their families who died that day.[5] The Ludlow Tent Colony Site was designated a National Historic Landmark on January 16, 2009, and dedicated on June 28, 2009.

Modern archeological investigation largely supports the strikers' reports of the event.

...

Mining was dangerous and difficult work. Colliers in Colorado were at constant risk for explosion, suffocation, and collapsing mine walls. In 1912, the death rate in Colorado's mines was 7.055 per 1,000 employees, compared to a national rate of 3.15...

Miners were generally paid according to tonnage of coal produced, while so-called "dead work", such as shoring up unstable roofs, was often unpaid. According to historian Thomas G. Andrews, the tonnage system drove many poor and ambitious colliers to gamble with their lives by neglecting precautions and taking on risk, with consequences that were often fatal. ...

Colliers had little opportunity to air their grievances. Many colliers resided in company towns, in which all land, real estate, and amenities were owned by the mine operator, and which were expressly designed to inculcate loyalty and squelch dissent. Welfare Capitalists believed that anger and unrest among the workers could be placated by raising colliers' standard of living, while subsuming it under company management. Company towns indeed brought tangible improvements to the lives of many colliers and their families, including larger houses, better medical care, and broader access to education.

However, ownership of the towns provided companies considerable control over all aspects of workers' lives, and this power was not always used to augment public welfare. Historian Philip S. Foner has described company towns as "feudal domain[s], with the company acting as lord and master. ... The 'law' consisted of the company rules. Curfews were imposed. Company guards - brutal thugs armed with machine guns and rifles loaded with soft-point bullets - would not admit any 'suspicious' stranger into the camp and would not permit any miner to leave." Furthermore, miners who raised the ire of the company were liable to find themselves and their families summarily evicted from their homes.

...

Frustrated by working conditions which they felt were unsafe and unjust, colliers increasingly turned to unionism. Nationwide, organized mines boasted 40 percent fewer fatalities than nonunion mines. Colorado miners had repeatedly attempted to unionize since the state's first strike in 1883. The Western Federation of Miners organized primarily hard rock miners in the gold and silver camps during the 1890s. Beginning in 1900, the UMWA began organizing coal miners in the western states, including southern Colorado. The UMWA decided to focus on the CF&I because of the company's harsh management tactics under the conservative and distant Rockefellers and other investors. To break or prevent strikes, the coal companies hired strike breakers, mainly from Mexico and southern and eastern Europe.

CF&I's management mixed immigrants of different nationalities in the mines, a practice which discouraged communication that might lead to organization.

The strike was organized by the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) against coal mining companies in Colorado.

The three biggest mining companies were the Rockefeller family-owned

Colorado Fuel & Iron Company (CF&I), the Rocky Mountain Fuel

Company (RMF), and the Victor-American Fuel Company (VAF). Ludlow,

located 12 miles (19 km) northwest of Trinidad, Colorado, is now a

ghost town. The massacre site is owned by the UMWA, which erected a

granite monument, in memory of the striking miners and their families

who died that day.

...

Despite attempts to suppress union activity, secret organizing

continued by the UMWA in the years leading up to 1913. Once everything

had been laid out according to their plan, the UMWA presented, on

behalf of coal miners,

a list of seven demands:

-Recognition of the union as bargaining agent

-An increase in tonnage rates (equivalent to a 10% wage increase)

-Enforcement of the eight-hour work day law

-Payment for "dead work" (laying track, timbering, handling impurities, etc.)

-Weight-checkmen elected by the workers (to keep company weightmen honest)

-The right to use any store, and choose their boarding houses and doctors

-Strict enforcement of Colorado's laws (such as mine safety rules,

abolition of scrip), and an end to the dreaded company guard system.

The major coal companies rejected the demands and in September 1913, the UMWA called a strike.

Those who went on strike were promptly evicted from their company

homes, and they moved to tent villages prepared by the UMWA, with tents

built on wood platforms and furnished with cast iron stoves on land

leased by the union in preparation for a strike.

Confrontations between striking miners and replacement workers, referred to as "scabs" by the union, often got out of control, resulting in deaths.

The company hired the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency to help break the

strike by protecting the replacement workers and otherwise making life

difficult for the strikers.

Baldwin-Felts had a reputation for aggressive strike breaking. Agents

shone searchlights on the tenvillages at night and randomly fired

into the tents, occasionally killing and maiming people.

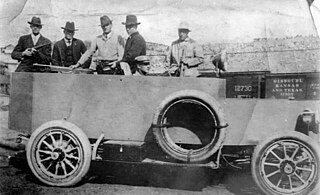

They used an

improvised armored car, mounted with a M1895 Colt-Browning machine gun

that the union called the "Death Special," to patrol the camp's

perimeters. The steel-covered car was built in the CF&I plant in

Pueblo from the chassis of a large touring sedan. Because of frequent

sniping on the tent colonies, miners dug protective pits beneath the

tents where they and their families could seek shelter.

...

As strike-related violence mounted, Colorado governor Elias M. Ammons

called in the Colorado National Guard on October 28. At first, the

Guard's appearance calmed the situation, but the sympathies of Guard

leaders lay with company management. Guard Adjutant-General John Chase,

who had served during the violent Cripple Creek strike 10 years earlier,

imposed a harsh regime. On March 10, 1914, the body of a replacement

worker was found on the railroad tracks near Forbes, Colorado. The

National Guard said that the man had been murdered by the strikers. In

retaliation, Chase ordered the Forbes tent colony destroyed. The attack

was launched while the inhabitants were attending a funeral of infants

who had died a few days earlier. The attack was witnessed by

photographer Lou Dold, whose images of the destruction appear often in

accounts of the strike.

The strikers persevered until the spring of 1914. By then, the state had run out of money to maintain the Guard, and was forced to recall them. The governor and the mining companies, fearing a breakdown in order, left two Guard units in southern Colorado and

allowed the coal companies to finance a residual militia consisting largely of CF&I camp guards in National Guard uniforms.

On the morning of April 20, the day after Easter was celebrated by the many Greek immigrants at Ludlow, three Guardsmen appeared at the camp ordering the release of a man they claimed was being held against his will. This request prompted the camp leader, Louis Tikas, to meet with a local militia commander at the train station in Ludlow village, a half mile (0.8 km) from the colony. While this meeting was progressing, two companies of militia installed a machine gun on a ridge near the camp and took a position along a rail route about half a mile south of Ludlow. Anticipating trouble, Tikas ran back to the camp. The miners, fearing for the safety of their families, set out to flank the militia positions. A firefight soon broke out.

|

| Coffins are marched through Trinidad, Colorado, at the funeral for victims of the Ludlow massacre |

The fighting raged for the entire day. The militia was reinforced by non-uniformed mine guards later in the afternoon. At dusk, a passing freight train stopped on the tracks in front of the Guards' machine gun placements, allowing many of the miners and their families to escape to an outcrop of hills to the east called the "Black Hills." By 7:00 p.m., the camp was in flames, and the militia descended on it and began to search and loot the camp. Louis Tikas had remained in the camp the entire day and was still there when the fire started. Tikas and two other men were captured by the militia. Tikas and Lt. Karl Linderfelt, commander of one of two Guard companies, had confronted each other several times in the previous months. While two militiamen held Tikas, Linderfelt broke a rifle butt over his head. Tikas and the other two captured miners were later found shot dead.

Tikas had been shot in the back. Their bodies lay along the Colorado and Southern Railway tracks for three days in full view of passing trains. The militia officers refused to allow them to be moved until a local of a railway union demanded the bodies be taken away for burial.

During the battle, four women and eleven children had been hiding in a pit beneath one tent, where they were trapped when the tent above them was set on fire. Two of the women and all of the children suffocated.

These deaths became a rallying cry for the UMWA, who called the incident the "Ludlow Massacre."

In addition to the fire victims, Louis Tikas and the other men who were shot to death, three company guards and one militiaman were killed in the day's fighting.

Although the UMWA failed to win recognition by the company, the

strike had a lasting impact both on conditions at the Colorado mines

and on labor relations nationally. John D. Rockefeller, Jr.

engaged labor relations experts, and future Canadian Prime Minister, W.

L. Mackenzie King to help him develop reforms for the mines and towns,

which included paved roads and recreational facilities, as well as

worker representation on committees dealing with working conditions,

safety, health, and recreation.

There was to be no discrimination of

workers who had belonged to unions, and the establishment of a company

union. The Rockefeller plan was accepted by the miners in a vote. (this sort of compromise only dooms the workers to re-live over and over again the same kind of oppression - my note)

|

| Ludlow monument, erected by the United Mine Workers of America |

Here are a few excerpts from Rockefeller's testimony, before the Congress:

CHAIRMAN: And you are willing to go on and let these killings take

place . . . rather than go out there and see if you might do something

to settle those conditions?

ROCKEFELLER: There is just one thing . . . which can be done, as things

are at present, to settle this strike, and that is to unionize the

camps; and our interest in labor is so profound . . . that interest

demands that the camps shall be open [nonunion] camps that we expect to

stand by the [Colorado Fuel and Iron Company] officers at any cost. . .

.

CHAIRMAN: And you will do that if it costs all your property and kills all your employees?

ROCKEFELLER: It is a great principle.

Rockefeller's version of the events - June 10, 1914

"There was no Ludlow massacre. The engagement started as a desperate fight for life by two small squads of militia against the entire tent colony … There were no women or children shot by the authorities of the State or representatives of the operators … While this loss of life is profoundly to be regretted, it is unjust in the extreme to lay it at the door of the defenders of law and property, who were in no slightest way responsible for it."