I received a comment from one of my readers in yesterday's

post, asking me to translate in English some of my older articles about the monetary system and gold (i have been blogging in Greek for 5 years now). However, before we get there, we must first explore some issues that are much more important, despite the fact that they are not discussed as much as gold, or the fall of the dollar-centric monetary system we have today.

Here's something from the Keynesian economist Joseph Stiglitz (source:

Vanity Fair):

[...] The argument has been made that the Fed caused the [1929] Depression by tightening money, and if only the Fed back then had increased the money supply—in other words, had done what the Fed has done today—a full-blown Depression would likely have been averted. In economics, it’s difficult to test hypotheses with controlled experiments of the kind the hard sciences can conduct. But the inability of the monetary expansion to counteract this current recession should forever lay to rest the idea that monetary policy was the prime culprit in the 1930s. The problem today, as it was then, is something else. The problem today is the so-called real economy. It’s a problem rooted in the kinds of jobs we have, the kind we need, and the kind we’re losing, and rooted as well in the kind of workers we want and the kind we don’t know what to do with. The real economy has been in a state of wrenching transition for decades, and its dislocations have never been squarely faced. A crisis of the real economy lies behind the Long Slump, just as it lay behind the Great Depression.

[...]

The banking crisis undoubtedly compounded all these problems, and extended and deepened the downturn. But any analysis of financial disruption has to begin with what started off the chain reaction.

[...]

The parallels between the story of the origin of the Great Depression and that of our Long Slump are strong. Back then we were moving from agriculture to manufacturing. Today we are moving from manufacturing to a service economy. The decline in manufacturing jobs has been dramatic—from about a third of the workforce 60 years ago to less than a tenth of it today. The pace has quickened markedly during the past decade. There are two reasons for the decline. One is greater productivity—the same dynamic that revolutionized agriculture and forced a majority of American farmers to look for work elsewhere. The other is globalization, which has sent millions of jobs overseas, to low-wage countries or those that have been investing more in infrastructure or technology. (As Greenwald has pointed out, most of the job loss in the 1990s was related to productivity increases, not to globalization.) Whatever the specific cause, the inevitable result is precisely the same as it was 80 years ago: a decline in income and jobs. The millions of jobless former factory workers once employed in cities such as Youngstown and Birmingham and Gary and Detroit are the modern-day equivalent of the Depression’s doomed farmers.

Stiglitz is right - today's problems go much deeper than just "a few greedy and reckless bankers". And he is also correct in identifying

globalization and

greater productivity as the two most important reasons for the decline in manufacturing jobs in the West.

We talked about globalization yesterday - so today we will talk about "greater productivity". Here's a chart about the USA:

Workers are becoming more and more productive, mainly due to great technological progress. Computers revolutionized production, and huge advances are occurring at a blistering pace (check out

3D "printing" of products for example, a revolutionary new way of producing goods with very little human effort required).

This increased productivity leads -obviously- to the production of more wealth than ever. And yet wages are stagnant at best - so who gets all this new wealth that is being produced if not the workers?

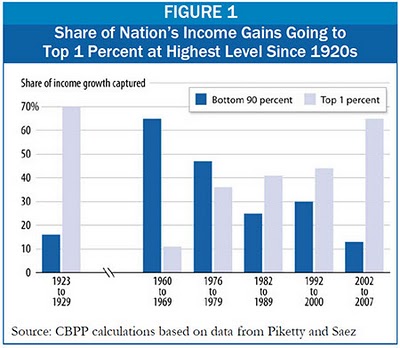

You guessed it, it's a handful of capitalists. Prof Rajan notes that

“of every dollar of real income growth that was generated between 1976 and 2007, 58 cents went to the top 1 per cent of households”. (Martin Wolf, Financial Times,

"Three years and new fault lines threaten").

Ever since the working class stopped "fighting the good fight" against being exploited by the capitalists, the capitalists have been able to seize a huge (and ever-increasing) portion of the wealth that is being created. Unions, workers political parties, etc. are "a thing of the past" - and off shoring production to China was "the nail in the coffin" for the Western workers.

Check out these charts, and compare them to the one above: You will see that they all follow a (VERY) similar pattern:

But let's get back to how greater productivity has resulted in the loss of jobs (and what can be done to fix this problem). Here's "a blast from the past" from Wikipedia:

Luddite fallacy

The Luddite fallacy is an opinion in development economics related to the belief that labour-saving technologies (i.e., technologies that increase output-per-worker) increase unemployment by reducing demand for labour. The concept is named after the Luddites of early nineteenth century England.

The original Luddites were hosiery and lace workers in Nottingham, England in 1811. They smashed knitting machines that embodied new labor-saving technology as a protest against unemployment, publicizing their actions in circulars mysteriously signed, "King Ludd."

This is considered fallacious because, according to neoclassical economists, labour-saving technologies will increase output per worker and thus the production of goods, causing the costs of goods to decline and demand for goods to increase. As a result, the demand for workers to produce those goods will not decrease. Thus, the "fallacy" of the Luddites lay in their assumption that employers would keep production constant by employing a smaller albeit more productive workforce instead of allowing production to grow while keeping workforce size constant.

[...]

Businessman Martin Ford, author of The Lights in the Tunnel: Automation, Accelerating Technology and the Economy of the Future, argues that the Luddite Fallacy is merely an historical observation, rather than a rule that applies indefinitely into the future. Ford describes how high technology improves geometrically, driving productivity gains which inevitably will outstrip human driven consumption increases that go up in a more linear fashion. Comparing consumption to a river of purchasing power, as companies along the river become more automated they extract more purchasing power from the river than they return in the form of employee wages and lower cost of goods. During the period that technology created jobs at the rate that they were made obsolete in other industries, Luddism was indeed a fallacy. Ford asks what the factual support is for the belief that the rate of job creation will match job destruction in perpetuity, especially in light of the phenomenon that increased capabilities of machines reduces the need for human labor in newly created enterprises at an exponential rate. Martin Ford proposes that like rivers, purchasing power be regarded as a public resource that industries cannot be allowed to pump dry. To do otherwise would fuel a deflationary spiral as lowered employment reduces purchasing power, forcing lower prices to compensate. The deflationary pressure perpetuates a cycle of shrinking of the economy as profitability plummets, resulting in further reduction in money put in the hands of worker-consumers. From the perspective of Ford and others such as Jeremy Rifkin who share this perspective, the Luddites may have simply been 200 years too early.

Besides job destruction, Luddites claimed that automation made the rich richer and the poor poorer. Economists have found that between 1980 and 2005, American jobs vulnerable to automation were lost, forcing workers into either low paying manual work or high paying technical work that is inherently difficult to automate. One study by MIT economists David Autor and David Dorn drew on evidence from the United States Department of Labor to show that automation caused sharp losses of middle class jobs, forcing a polarization of wages and greater income inequality. The phenomenon of polarization due to automation is not confined to the US, also occurring in 15 of 16 European countries for which data is available.

As robotics and artificial intelligence develop further, even many skilled jobs may be threatened. Technologies such as machine learning may ultimately allow computers to do many knowledge-based jobs that require significant education. This may result in substantial unemployment at all skill levels, stagnant or falling wages for most workers, and increased concentration of income and wealth as the owners of capital capture an ever larger fraction of the economy. This in turn could lead to depressed consumer spending and economic growth as the bulk of the population lacks sufficient discretionary income to purchase the products and services produced by the economy.

Photo of Luddites "raging against the machine" (literally): Luddism tries to turn back the wheel of time, instead of trying to use the new technological advances in a way that benefits the workers.

Machines aren't the enemy, the control of production by a handful of capitalists is.

What Ford is describing is what K.Marx identified more accurately as "a tendency of the rate of profit to fall" - Marx understood that this is just a tendency, not a rule, as there are many factors that can counteract this tendency, such as more intense exploitation of labour, cheaper raw materials, etc.

It is however true that utilizing new technologies in out times has created less jobs than it has destroyed.

It's not the first time this has happened in history:

A century ago, the workers realized that there was no point in destroying the machines - instead, they started to make a demand for the

eight-hour day and coined the slogan

"Eight hours labour, Eight hours recreation, Eight hours rest". Here's

wikipedia on the subject:

The eight-hour day movement or 40-hour week movement, also known as the short-time movement, had its origins in the Industrial Revolution in Britain, where industrial production in large factories transformed working life and imposed long hours and poor working conditions. With working conditions unregulated, the health, welfare and morale of working people suffered. The use of child labour was common. The working day could range from 10 to 16 hours for six days a week.

Is this not what is happening

right now, especially in Asia? And is this not what the future looks like for the workers of the West?

What's the answer to all this? Unfortunately, the Chinese workers are still "too hungry" in order to organize and demand something like the 8-hour day (although their protests are becoming more frequent and organized).

As for the Western workers, they still remember (?) some of their history. Especially the European workers, who still celebrate Mayday and the worker's uprising in Chicago which resulted in the formal institution of the 8-hour day (incredibly, the American workers have very little memory of these events, even though they took place in the USA).

Here's something from Paul Lafargue's famous pamphlet

"The Right To Be Lazy", which played a key role in helping the workers of his era (just before the Mayday uprising) realize that they need to use the technological advances of the industrial revolution to their advantage, instead of trying to destroy them:

[...] “The prejudice of slavery dominated the minds of Pythagoras and Aristotle,” – this has been written disdainfully; and yet Aristotle foresaw: “that if every tool could by itself execute its proper function, as the masterpieces of Daedalus moved themselves or as the tripods of Vulcan set themselves spontaneously at their sacred work; if for example the shuttles of the weavers did their own weaving, the foreman of the workshop would have no more need of helpers, nor the master of slaves.”

Aristotle’s dream is our reality.

Our machines, with breath of fire, with limbs of unwearying steel, with fruitfulness, wonderful inexhaustible, accomplish by themselves with docility their sacred labor. And nevertheless the genius of the great philosophers of capitalism remains dominated by the prejudice of the wage system, worst of slaveries. They do not yet understand that the machine is the saviour of humanity, the god who shall redeem man from the sordidae artes and from working for hire, the god who shall give him leisure and liberty.

And yet, today nobody talks about decreasing the working day. But as long as billions of workers in Asia work 10, 12 or even 16 hours/day, and get very little in return, it is pretty clear that a lot of workers, especially in the West, will remain unemployed and starve to death.

These workers "are not competitive enough", so they will live (or die) in extreme poverty. This process will result in many deaths, and much more misery for the workers, yet this is the only way for the capitalists to make them competitive enough, so that their profits can be maximized. Austerity is obviously not a strategy to restore growth, it is a strategy that only aims to reducing the wages of the future generations of workers, even if it re-enforces the economic downturn in the short-term. It is only when the workers have accepted poverty as a way of life that the capitalists will restart investing in the West. Until then, the workers will be left to starve.

The working class MUST demand a shorter working day - for example, even if we could reduce the working day by only an hour, (7-hour day instead of an 8-hour day), we would in effect have created a new job for every 7 workers (instead of employing 7 workers for 8 hours/day, we could employ 8 workers for 7 hours/day).

The problem is of course that the capitalists are the ones in charge, not the workers. And the capitalists will never accept this, as it reduces their profits. And even if some of them do, the rest of them will not, and they latter will dominate over the former, since they will have a big competitive advantage (they exploit the workers more, so they can sell their products at cheaper prices, or produce more products, etc.).

Even Keynes predicted that by 2030, we'd be working a 15-hour week, mainly thanks to greater productivity. (source:

Guardian) .

Keynes's mistake was that he underestimated the ability of the capitalists to keep all the newly created wealth for themselves, by increasing the rate of exploitation of the workers.

Yes, capitalism has created the technology to work for only 15 hours/week. But it has also created a class of oligarchs who prefer to live at the expense of the workers, and make some of them work for 15 hours/day, and leave some others unemployed and with no income at all. And it is this realization that has created the incentive for the workers to overthrow the capitalists, or face a life in poverty, even a death of starvation.

The Chinese Democracy World Tour: Guns n Roses were trying to criticize China's version of democracy - if only they know that capitalists think of China's version of democracy as a "role model"...

The Chinese Democracy World Tour: Guns n Roses were trying to criticize China's version of democracy - if only they know that capitalists think of China's version of democracy as a "role model"...